Hidden Objects: The

Stories They Could Tell -- Characters

By

Becky Waxman

I've been exploring the world of

Interactive Hidden Object Games (IHOGs) in previous editorials, including

innovations in way Hidden Object challenges are presented, and the

incorporation of adventure game elements: more puzzles and inventory

item challenges, and the opportunity to explore in larger environments. In

case you haven't read previous editorials, IHOGs are games with Hidden

Object (HO) screens where one or more of the selected items are later used

as elements in inventory item puzzles.

Now I turn to story and characterization.

I've found IHOGs to be an excellent source for studying storytelling in

games -- partly because they are available in great variety, and partly

because they tend to be shorter than "core" games. In other words, they

provide an efficient way to experience different approaches and story

types, much like comparing or analyzing short stories rather than novels.

In this editorial, I'll focus on IHOGs with intriguing stories in which

events and puzzles are character-driven.

Character-Driven Games and Suiting Puzzles

to the Characters

Character-driven IHOGs are those where the

developer has given the main characters unique personalities, and the

gamer begins to know them well enough to be able to predict how they will

respond to various events. These games reveal character by putting the

protagonist in situations where there is conflict, mystery, and (often)

danger that is augmented or caused by non-player characters (NPCs) in the

game. These NPCs have agendas that help or hinder (or do one while

appearing to do the other). How the protagonist reacts in various

situations highlights his or her personality. Also revealing is which NPCs

the protagonist chooses to trust, and why.

One effective technique games can use to

increase knowledge of the main character is to create challenges that tap

into the protagonist's area of expertise. A lab technician's analytical

skill, or a historian's knowledge of the past, or the mental powers of a

psychic are not just central to defining the protagonist's personality --

they can also bolster puzzle/story integration. Admittedly, in the context

of a game, these skills trend more toward entertainment than heavy-duty

realism. Still, a protagonist doing puzzle-like "work" consistent with his

occupational or personal skill increases immersion and suits the story.

IHOGs that draw the protagonists' talents

or special abilities into the gameplay have more dialog and/or more cut

scenes than the typical casual game. Antagonists are often hiding in plain

sight -- a colleague or a neighbor -- and the protagonists interact with

them (sometimes several times) before discovering their villainy.

A Short Detour into the Idea of Linear

Progression in Games

The character-driven IHOGs I played also

tended to be quite linear. What do I mean by "linear"? Stories in books

and films typically begin at the beginning and unfold step-by-step. Though

some experimental books and films attempt to give a sense of nonlinearity

(often through the use of flashbacks), these are not the norm.

Like books and films, IHOGs with a linear

structure don't allow the gamer to walk around the environments, but

present one screen with its Hidden Objects, puzzles, and character

interaction, then present the next screen, and so on.

A linear progression in a game allows the

developer to exercise complete control over the story elements, including

when and how they are presented, keeping the gamer "on the right page." In

theory, a linear structure should make complex stories easier to write,

with more nuanced, plot-progressing, personality-descriptive dialog.

I expected character-driven IHOGS to

exhibit instances of witty, character-revealing dialog exchanges, but

(with a few exceptions, some of which are featured below) I was

disappointed. Why, I wondered, haven't designers taken advantage of this

subgenre to write elaborate dialogs?

I discovered that -- for a significant

percentage of gamers -- the "casual experience" means skipping the story

altogether, especially if it means that the characters engage in long

conversations. This preference has apparently discouraged IHOG designers

from writing lengthy dialogs like those seen in adventure games like

The Longest Journey or The Moment of Silence.

IHOG designers may someday write dialog

comparable to that in (for instance) the classic novel Pride and

Prejudice. But for now, they seem more concerned with keeping dialogs

from overwhelming the puzzles and HO screens.

Five Examples of Character-Driven

Interactive Hidden Object Games

Though linearity hasn't influenced dialogs

as much as I expected, linearity in character-driven IHOGS makes a twisty

plot possible in a small space. The plot is often fleshed out in brief,

graphic-novel-like cut scenes and the game contains puzzles suited to the

protagonists' specific abilities. Below I've provided descriptions of five

character-driven games. For variety, I've included IHOGs that can loosely

be classified as a thriller, a romance, a mystery with police procedural

elements, a mystery with pulp fiction elements, and a fantasy spoof.

*Note: I'm aware that

many gamers partner with their young children to play IHOGs. I've put an

asterisk in front of each game that is more appropriate for teens and up.

Unlike the games I discussed in previous IHOG editorials, most of the

games described below are not appropriate for young children -- perhaps

because deep stories delve into the darker side of human nature.

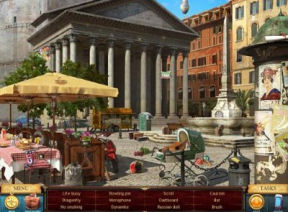

*Rhianna Ford & The Da Vinci Letter

Rhianna Ford, an antiquities expert, is in

Rome examining a letter allegedly written by the hand of Leonardo da

Vinci. She is haunted by the disappearance of her husband, also in Rome,

earlier that year. She stumbles across a crime as it is committed, and

from then on she is consumed with finding out what is going on behind the

scenes, and whether her husband's disappearance is linked to a criminal

conspiracy.

This casual thriller is quite linear, and

the tight structure allows the story to unfold at a fast pace, with many

characters potentially implicated in the conspiracy. It contains frequent,

brief dialogs. Memorable character portrayals include Rhianna, who is

terrified to discover the truth about her husband, D'Agostino the cynical

Italian police inspector, and Paulo the geeky exercise addict. The gamer's

attitude toward the characters and their motives changes, reverses, or

becomes ambiguous as Rhianna's knowledge about them deepens.

Environments are photorealistic and

beautifully lit, giving the gamer many chances to see intriguing museum

artifacts, as well as glimpses of sights around Rome. Tension-inducing

music with unusual rhythms and sounds adds to the atmosphere. The only

downside -- the voiced, cartoon-like cut scenes are decidedly different

visually, making them unintentionally disruptive and distracting.

Locations are single screens and always

contain a "find" list. In addition to the HO gameplay, the game has well

integrated puzzles (some of which spring from the heroine's art history

expertise), including comparing ink and fiber samples and using an

ultraviolet light to discover hidden symbols. Adventure gamers will

recognize Rhianna Ford & The Da Vinci Letter designer Steve Ince of

Broken Sword fame.

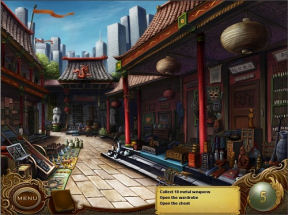

*Tiger Eye Part 1: Curse of the Riddle Box

Based on a romantic story by author

Marjorie M. Liu, Tiger Eye features Dela Reese, a young woman with

as-yet-untested paranormal abilities (particularly the ability to shape

metal) and Hari, a magical being forced to serve a series of masters over

the centuries. The tale begins in modern day China, where Dela and Hari

first meet and where the evil pursuing them first attempts to take hold.

Frequent graphic-novel-like cut scenes,

fully voiced, portray the couple's adventures. I've never seen a story

quite like it in a game. It ricochets between drama, danger and lust and

snuggles up next to melodrama. (Keep a fire extinguisher handy just in

case a torrid scene sets your monitor aflame.) Themes include the effects

of magic breaking into the real world, and how oppression and cruelty

shape a person's character. The game has a cliffhanger ending. It'll be

fun to see how the story unfolds through the sequel.

Graphics are colorful and cartoon-like,

and the game is very linear. The HO searches are for multiples of items in

the same category (find 10 metal weapons, for example).

Dela's psychic abilities increase in

strength and importance as the story progresses. These powers are

introduced in game form through an untimed match three sequence, where

squares are cleared away so that a vision is gradually revealed. There are

also sequences during which Dela undergoes a form of psychic attack and

activates mind defenses -- this is represented by a neuron connection game

that starts out easy and then becomes dastardly.

Overall the puzzles in this games are

frequent and varied (though some puzzles repeat through several

iterations). Expect pattern and shape analysis, inventory challenges,

matching, jigsaws, and even a shopping challenge. I particularly enjoyed

the word puzzles, a couple of which were types I hadn't encountered

before.

*James Patterson Women's Murder Club:

Little Black Lies

This game features the characters from

James Patterson's novels about a group of truth-seeking professionals who

form the Women's Murder Club (WMC). You alternately assume the roles of

three members of an investigatory team: Lindsay Boxer (detective), Claire

Washburn (medical examiner), and Cindy Thomas (journalist). When a friend

of Claire's is murdered, the WMC springs into action to find out how the

actions of a cult, supposedly disbanded years earlier, may be disrupting

the peace of an idyllic spot on the California coast.

Many of the game's puzzles are related to

tasks in the forensics lab when you play as Claire. A few are surprisingly

difficult, especially the skeleton assembly task. I was intrigued to see a

couple of word puzzles in addition to the traditional HO "find" lists -- a

crossword puzzle and a riddle-like travel challenge. (This game

incorporates a free strategy guide if you get stuck.)

The game's graphical style is

naturalistic, with the locations authentically portraying small town

America. The NPCs also suit the small town atmosphere -- including Beverly

Connors, the librarian who can't decide whether to be helpful or hostile,

and Sympathy Morgan, the laidback owner of the craft shop at The Crystal

Barn. Little Black Lies has brief and to-the-point dialogs,

competently voiced. A map with hotlinks to the various locations is

included.

This game is less linear than the previous

two I've described above, but some degree of linearity is enforced by

changing roles to play the various protagonists. There's also less

character growth than in the first two games -- mostly, I suspect, because

the Women's Murder Club is a long-running series, where the gamer

becomes gradually acquainted with the main characters over several games.

After the murderer is revealed in

Little Black Lies, the Epilogue takes you back in time and puts you in

the role of a character desperately trying to cover up a crime. It was a

different type of role than I've played in a casual game, disconcerting

and chilling. Jane Jensen, designer of the Gabriel Knight adventure

games, was involved with the game's design as Creative Director.

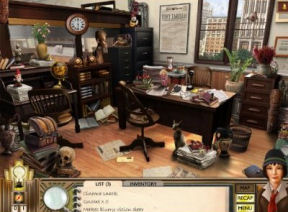

*Valerie Porter and the Scarlet Scandal

Set in the Roaring Twenties in urban

America, Valerie Porter and the Scarlet Scandal follows the

adventures of a fledgling newspaper journalist as she investigates the

murder of a film star. The game starts with the murder, goes through an

extensive flashback, and then continues with the investigation in a mostly

linear fashion.

Graphics are clear, bright, and somewhat

stylized, and jazzy music plays in the background. All the characters are

competently voiced. Valerie is making her way in a world that clearly

favors male journalists -- her boss regularly treats her like an errand

girl.

Several puzzles are related to Valerie's

writing skills, including word searches, finding the correct words for a

feature story, and spelling out headlines. The game also contains photo

adjustment, persuasion and mechanical assembly challenges. HOs are "find"

lists, sometimes with multiple similar objects, and sometimes with

descriptive phrases rather than single words. You can also click to see

silhouette shapes for the items on the list.

Valerie's competence in ferreting out

sensationalist secrets increases through the game, as does her tendency to

remove items from any room in which she is left alone. (Note to self: if a

reporter asks for an interview, hide all embarrassing personal

belongings.) Other characters tend toward the stereotypical -- the

demanding editor, the slick politician, the gruff professional boxer. (The

most memorable and non-stereotypical NPC is Valerie's mentor Terry Morgan,

who has established herself as an ace female reporter despite the odds

against her.) Stereotypes are used in a thought-provoking way here,

however, as some of the characters react unexpectedly when the story

reaches its culmination.

Magic Academy II

This is the tale of an ambitious young

Magic Academy graduate who is determined to work her way onto the powerful

Magician's Council. She approaches the Council at a time when it's in a

state of near chaos. Some of the members think that a traitor has

unleashed a demon into their castle fortress. Others deny that this would

even be possible. Suspicions leapfrog among the magicians, and settle on

Irene's sister, Annie, who works with foreign emissaries at the fortress.

Determined to prove her worth (and clear

her sister's name), Irene sets out to learn as much as she can about the

demon and a mysterious box that exhibits demonic traces. She works with

various aspects of magic -- runes, potions, and magical energy. Irene also

performs many tasks, often related to magic that is now out of control.

The loss of control is shown through the

game's challenges. For example, the eccentric magicians at the fortress

create illusions they can't remove (spot-the-difference challenges),

forget how to access certain rooms in the castle (inventory challenges)

and accidentally change all the insects in the castle into animals (HO

challenges). HO challenges feature item silhouettes, multiples of the same

item, and a few "find" lists. Often objects are in drawers or behind

curtains. The game also contains a full complement of puzzles, a few of

which are mildly timed. Most of the puzzles are familiar types, but others

are fresh -- the magical well, for instance, and the bouncing marble

challenge.

Graphics are naturalistic, quaint and

colorful. Pleasant orchestral music plays in the background. The story is

linear; dialogs are droll and often tongue-in-cheek. All are fully voiced.

Voiceovers are competent, though Irene sounds a tad too young and eager,

especially for a magician with so much range and talent.

Memorable NPCs include Irene's sister

Annie who looks like Queen Amidala (minus the face paint) and Alchemist

Ferrous, who can believe six impossible things before breakfast and wants

to use magic to enable them.

One downside: Magic Academy II --

developed by NevoSoft, the same developers who created Vampireville

-- contains a similar save system. If you quit mid-chapter, you start

again at the beginning of that chapter when you resume.

Conclusion

In this editorial I've discussed one

approach to "playing a story" -- the character-driven Interactive Hidden

Object Game. I've also provided a handful of examples for playing and

pondering. There are many more aspects to discuss about storytelling in

casual games but this is, at least, a start.

To recap: in character-driven IHOGs, you

as the player become acquainted with the protagonist, feel the force of

her distinct personality, see how other characters react to this person,

and are encouraged to begin to think like the protagonist. These games

tend to have complex stories that are fairly (or very) linear, frequent

interaction with NPCs, and puzzles based on the protagonist's skills or

knowledge. Linearity brings a compression of action and events so the

story packs more punch.

Look to this space to see more discussion

of stories in casual games. Coming up next: "Hidden Objects: The Stories

They Could Tell -- Quests."

**Note: some of the ideas for this article

were influenced by Writing for Video Games, a book by Steve Ince.