Hidden Objects: The

Stories They Could Tell -- Quests

By Becky Waxman

This is the

second in a series of editorials about storytelling in Interactive Hidden

Object Games (IHOGs). In a

previous editorial I discussed character-driven IHOGs, which

tend to be linear, with well defined characters, twisty plots, and

challenges that often spring from the protagonist's talents or abilities.

The games I am about to

describe are quite different from character-driven games and have a

greater sense of freedom. The personality of the protagonist is not as

developed as in character-driven games, and the plot is usually less

complex. The game environments are much larger and encourage nonlinear

exploration -- allowing the gamer to choose what to examine first and (to

some extent) the order in which to take on challenges. (This may involve

significant back-and-forthing through the gameworld.)

The gamer slips into the

protagonist's role, not by solving puzzles related to the protagonist's

character or occupation, but by being caught up in the urgency of a quest.

Most of the puzzles spring from the forbidding, often fantastical

environments that the hero sets out to explore, understand, or conquer.

Some examples: the hero might be challenged to rescue people, restore

natural environments, repair mechanisms, explore under water, enable

portals to alternate realities, travel in time, bypass guards or security

systems, and use magical or chemical concoctions.

The Hero Quest

The hero quest or hero's

journey is a common narrative theme in books, films, and games, sending

the protagonist to an unfamiliar, foreign place or to a familiar place

that has been radically transformed by time or disaster. In order to "find

himself," the hero must first lose himself and then struggle to discover a

way back. The quest is a test of character; courage and self-sacrifice are

common themes. The quest can also be a journey into hidden or unpleasant

truths, where knowledge acquired or actions taken are essential for

setting things right upon the hero's return. The stakes are always high,

with the fate of a family, a village or even a civilization resting on the

hero's shoulders.

Non-player characters (NPCs)

encountered on quests may be victims or allies of the villain or even

heroes who have previously failed the quest. The NPCs sometimes have

knowledge that the hero needs, or they guard artifacts and ancient/sacred

places. Often they are not fully developed as characters, but are there as

gatekeepers or task-givers.

The villain in IHOG hero

quests usually doesn't get a lot of screen time. He may be a shadowy

character with one particular ambition -- eternal youth, absolute power,

or revenge. His influence is felt in the environment or through the

actions of other characters. The hero must learn enough about the villain

to locate and/or identify him and then (since a handy policeman is never

around to make an arrest) figure out how to defeat him. Sometimes the

environment itself becomes a "villain" in the form of storms or natural

disasters.

Below are six examples of

IHOGs with a hero quest (or heroine quest, since many of the protagonists

are female). These could be broadly classified as games with fantasy,

historical fantasy, disaster, science fiction, and horror themes. I've

also included a game that would probably best be described as a dark fairy

tale.

*Note:

I'm aware that many gamers partner with their young

children to play IHOGs. I've put an asterisk in front of each game that is

more appropriate for teens and up, rather than young children. There were

two close calls. Shaolin Mystery: Tale of the

Jade Dragon Staff

is

appropriate for children until the end of the story, when there's one

brief but indelibly violent image. Time Dreamer has a couple of

vulgarities in it, but otherwise is appropriate for children, except that

the atmosphere is dark and the plot moves between different time periods,

so that a child might have trouble following it.

A Gypsy's Tale: The Tower of Secrets

Set in a fantasy world not unlike that of

the King's Quest games, A Gypsy's Tale contains the most

nonlinear story of all the games discussed here. You assume the role of

Reylin, a wandering gypsy hired to break the curse on a tower. You learn

that there's more to breaking curses than originally envisioned and that

much goes on beneath the surface.

The graphics are painterly and nostalgic.

The atmosphere is quaint, with forest scenes and dwellings that would

accommodate a hobbit, should one drop by. The environments are meant to

charm and entice; until the game's end they are lovely and welcoming,

though evil's influence is also apparent.

The game starts out slowly, but picks up

as you begin to meet the characters, including a gnome, a water horse and

a real estate agent (the interactions are brief and the characters are not

voiced).

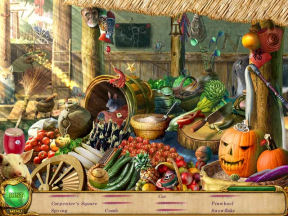

The Hidden Object (HO) challenges include

finding items in various categories and searching for items or parts of

items shown as images surrounding a wheel. In the latter instance, once

found, the items automatically combine to form the finished object.

Puzzles include inventory challenges, pattern puzzles, and creating

potions and other concoctions.

Many tasks involve solving something

that's gone wrong in the environment -- bringing a garden back to life,

fixing a fountain, making it rain, healing a deer. You'll nearly always be

doing several tasks at once. You can wander through the gameworld, but

there's also a map with hotlinks. This nonlinearity works with the story,

partly because the map makes it easy to visit every location to see if

anything has changed or if the characters have something new to say. (One

downside to the game's nonlinearity is the role of invisible triggers; if

you miss a trigger you might have to resort to the hint system in order to

progress.) The game toys with your expectations as to how a story in a

fantasy world ought to unfold, and it provides a satisfying ending.

*Shaolin Mystery: Tale of the Jade Dragon

Staff

This is a journey through ancient China

and through fantasy environments that house fragments of the fabled jade

dragon staff. Our heroine -- a young woman named Yu -- watches as a

childhood friend, Zihao, is arrested by the Imperial guards. She manages

to talk to him in prison, and he reveals that he is the true emperor,

trying to escape his power-usurping uncle. Zihao's execution looms unless

Yu can reassemble the fabled jade dragon staff, which will allow Zihao to

take his rightful place on the throne.

Yu is loyal, resourceful and determined,

though not much else of her personality is revealed. The villain is a

distant figure -- his rule is characterized by encounters with the

oppressed city dwellers, rebels, and prison guards. The story unfolds in

chapters, with cut scenes showing still images, and with a narration

voiced by the heroine between chapters (character dialogs aren't voiced).

By game's end, Yu has witnessed strange and wonderful sights in the realms

of myth, and is beginning to understand the depth of magic and myth.

The graphics appear hand drawn and include

city locations as well as magical environments with monumental structures,

spectacular flora and odd fauna. Varied animations add a sense of ambient

movement. The locations -- especially later in the game -- evoke a sense

of mystery and awe; they are meant to fascinate and intimidate. Each

location has creatures to converse with, though dialogs are so brief that

character interaction is overwhelmed by the mystery and color of the

landscapes.

Puzzles include inventory challenges,

pattern analysis, assembly challenges and mini-games with Asian themes.

You will be manipulating the environment -- replacing missing crystals,

adjusting weights, snaring insects, awakening dormant spirits. Each

location has HO "find" lists with unusual objects to admire. Each location

also contains images arranged in a circle that depict items that must be

found. The image wheel challenges seemed to fit the environments and the

story better than the "find" lists. A diary, or some way to provide a bit

of background information about the fantastical places Yu explores, would

have satisfied this gamer's desire to know even more.

*Nightmare on the Pacific (Premier

Edition)

The good ship "Neptune" has wandered into

the path of a hurricane, and during a brief lull, rescue helicopters

attempt to evacuate everyone on board. One passenger, Sarah Brooks,

chooses to remain on the sinking ship because she knows that her children

and husband are trapped somewhere below. Can she find them and get them

out before the ship goes under?

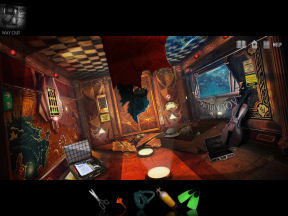

This game uses a current day setting and

naturalistic graphics, but the normally safe environment of a cruise ship

has become a horrifying mockery of itself, as the ship founders, breaks in

half, and part of it turns upside-down. You are dealing with rising water,

failing electrical systems, locked doors, massive chunks of debris, and

even an opportunistic shark.

I didn't expect the drama of a disaster

story to work well with HO "find" lists, but Nightmare on the Pacific

combines the two surprisingly well. It makes sense, under the

circumstances, that items have fallen, skidded across the deck, and ended

up in a heap. It's fascinating to see what has happened to the inside of

the ship as the storm slowly rips it apart. In the pub area, for instance,

you could have a drink at the underside of the bar, should you choose.

(Bottom's up!) The groaning of the ship's timbers and various watery

noises are accompanied by ominous music that merges with the sound layer.

The main character's voiceovers are believable and add to the atmosphere

of urgency and strain.

In addition to the "find" lists, the game

contains inventory puzzles, and challenges in which you unlock or force

doors to open, restore valves, put out a fire and remove a chandelier. The

Premiere Edition includes a prequel which adds a brief backstory and lets

you see a small portion of the ship before the storm strikes.

Time Dreamer

This game has a creepy atmosphere and a

surprisingly sophisticated story, especially for a game that otherwise

fits the definition of a hero quest. You awaken from a coma to discover

that your father (a research scientist) is now dead and your hometown is

being taken over by your father's employer -- a corporation called INFAM

(it isn't clear at first if this is supposed to have the sense of "in the

family" or "infamous").

You are visited by a friend of your

father's named Giovanni, who has steely eyes and an odd little moustache.

Giovanni explains that you have an unusual talent -- you can travel

through time while you sleep, theoretically granting you the chance to

change reality. Giovanni wants to help you mold the environments in the

past so that your father will still be alive in the present.

In Time Dreamer, you not only

travel into the past, but also into the future. Graphics in the game are

sometimes naturalistic, and at other times surreal, and the locations are

more restrictive than in the other hero quest games I've described. You

visit your home at various stages in time, plus the INFAM offices -- going

from the corporation's modest beginnings to its futuristic culmination.

Quirky music adds greatly to the atmosphere.

During your travels, you will interact

briefly with other characters; dialogs are unvoiced. You will uncover

family secrets and evidence of dirty dealing. As your understanding

increases (despite slip-ups), you begin to make better time-related

decisions.

The game features inventory puzzles,

sabotage challenges and HO "find" lists, some with a wacky sense of humor.

Certain items foreshadow events in the game and perhaps give an alternate

explanation for what's going on. On the "casual" setting, you can choose

to see items in silhouette in addition to the word descriptions.

The plot in Time Dreamer advances

in nonlinear chunks; at points I felt as though I was hanging onto the

correct sequence of events by mere fingertips. Reading the diary helps

greatly to keep track of time periods, what's going on in each, and the

results of the changes made in time.

*Nightfall Mysteries: Asylum Conspiracy

Strong-willed, and well-intentioned,

Christine has left her home and travelled to an isolated island after

receiving a letter from her grandfather. Cut off from civilization, she

finds an (almost) abandoned asylum.

Christine's task is to find out what has

happened in the past at this ominous place, and, with the help of others,

decide what to do about it. The game gradually gives up its secrets as

Christine puzzles her way through the asylum and deep into the island.

Cassette tapes left by previous inhabitants give a patchwork auditory

record of events, and tease as much as they explain.

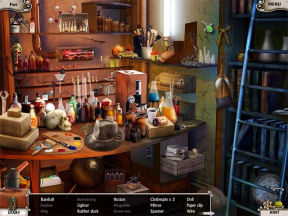

Challenges include inventory puzzles,

placing items in the correct order, and solving complicated locks. The

asylum is built to impede anyone attempting access -- many of the tasks

involve bypassing the security measures. Much of the place is tumbling

down, so that fixing machinery to gain access is also important, as is

creative use of certain medical equipment. The game contains traditional,

close-up "find" lists. Sometimes the HO screens are eerily beautiful.

Other times they are distinctly unsettling -- especially the ones with a

bizarre sense of humor.

Asylum Conspiracy

has an antique, hand painted look, sometimes glowing with iridescent

light. Odd angles throw the viewer off guard. The various locations speak

of terror, pain, luxury and cruelty. (The notebook contains a map, but it

is not hot linked.) You wouldn't expect an asylum to draw the you in, but

somehow this one does.

Dialogs with a handful of characters are

brief. Voiceovers are excellent. You learn snippets of the characters'

histories -- enough to make them sympathetic, though not enough to feel

deeply involved. They seem alarmingly willing to let Christine continue on

alone to confront an ultimate evil. By the end of the game, you have an

inkling as to what is behind the horror, and will probably be wildly

curious as to how the villain has managed to propagate this scheme for so

long.

*PuppetShow: Souls of the Innocent

Children in a European village have fallen

asleep and can't wake up. You assume the role of an investigator trying to

figure out the cause and provide a cure. Clues in the village lead to an

abandoned castle in a barren valley, occupied by hundreds of animatronic

"puppets." These puppets are similar to the automatons in Syberia,

though definitely creepier. They are the chief characters you meet. (The

game is not voiced.)

Souls of the Innocent

is an odd combination -- a game with dark, sinister themes, yet bright,

hand drawn graphics. The castle is equipped with bizarre contraptions,

many different types of locks and keys, and signs of genius devolving into

madness. An ancient evil, long dormant, has been awaiting the right

catalyst in order to be revived.

As the quest progresses, you encounter

different variations of the human form -- the puppets, dolls, figures in

paintings, skeletons -- most in a stage of disassembly, decay, or

entrapment. Animations in the game are varied and add considerably to the

queasiness of the atmosphere, as does the unusual background music with

punctuated vocals. Despite the delicate use of color, the environments are

meant to disturb and frighten. The whole effect is wrenching enough that

at one point I abandoned the game and then returned because I had to know

how it was all going to turn out.

Puzzles test your abilities at pattern

analysis, inventory application, and (occasionally) your willingness to

experiment. Repairing, using, or stopping the puppets is part of the

challenge, as is fixing machinery and getting past unusual locks and other

types of barriers. Traditional "find" lists make up the HO challenges.

The castle you are exploring contains

three towers, each harder to reach than the last -- and by the time you

finally mount the steps into the third tower, you are wildly curious as to

what is finally going to be revealed.

Conclusion

To recap: in hero quest Interactive Hidden

Object Games, you are interacting with challenging, expansive, strange and

exotic environments -- much more than with other characters. You have some

degree of control over where you go and the order in which you accomplish

some of the tasks. Nonlinearity often means that the story is fairly

simple and the pace may be uneven. If the story is complex, nonlinearity

means that keeping track of events can be a challenge in itself.

Random Thoughts

Some thoughts after playing the hero quest

IHOGS described above.

Backstory

A few of these games would have been more

satisfying if they had provided more backstory. I personally enjoy

learning more about the gameworld in diaries and journals -- but I know

that extensive text passages aren't necessarily every casual gamer's

favorite thing. Two of the games provide backstory in different,

intriguing ways. Nightfall Mysteries: Asylum Conspiracy contains

cassette tapes scattered throughout the locations that can be played to

give a sense of how the Asylum employees were faring before Christine

arrived. Nightmare on the Pacific (Premiere Edition) provides a

playable prequel level after the main game is complete.

Going at Your Own Pace

Hero quest games can be full

of dramatic tension (Nightmare on the Pacific) or they can be more

contemplative (Shaolin Mystery: Tale of the Jade Dragon Staff). The

nonlinear exploration in these games lets the gamer examine everything

much more closely than she could if this same story was being told in (for

instance) the form of a film. Taking your time and drinking it all in does

tend to reduce dramatic tension -- since the gamer controls the pace, the

pace can become quite slow. As a slow gamer myself, I just want to confirm

that games that give the option to take things slowly are just as

enjoyable (in fact, more so) than games that speed things up by using

timed challenges. Slow gamers appreciate having a "relaxed" vs. "timed"

option, and, as a result, probably come through the experience with an

increased appreciation for all the details in the gameworld.

Heroines and the Men they

Leave Behind

An intriguing aspect of IHOG

hero quests is the issue of the protagonist's gender. Most IHOGs have

female protagonists (this is common in casual games, since the majority of

casual gamers are female). Two of the games noted above involve storylines

in which an able bodied male character with knowledge of the environment

chooses to stay behind while the female protagonist goes on to (what is

for her) an unfamiliar place filled with evils and/or physical dangers.

For the heroine to take on dangers that no one else can face suits the

theme of a hero quest, but this sometimes involves downright odd decisions

on the part of male NPCs. If capable, strong men choose to stay behind,

they need a good reason. Taking care of a child -- the excuse in the games

I've played -- isn't a sufficient reason.

First, Admire Fantastical

Environments -- Second, Look for a Pestle, a Pear and a Peanut

Finally, the issue of "find"

lists. In games like hero quests that are focused on environment-based

challenges, close-up "find" lists -- especially those with items that have

nothing to do with the story or the environment -- tend to disrupt this

gamer's sense of immersion. Partly it's because I have to suddenly start

thinking verbally (keeping random words in memory, most of which have

nothing to do with the quest). Partly it's because the close-up areas are

often different in appearance (and sometimes different in theme) than the

rest of the gameworld. In my experience with hero quest games, HO

challenges that use image wheels or fragments of objects are better at

retaining that sense of immersion in the environments, unless great care

is taken to make the "find" lists suit the environment and overall theme.

Coming Up Next

Look to this space to see more discussion

of stories in casual games. But first, a slight detour into a different

theme, the next installment in this series: "Casual Adventures -- Testing

the Atmosphere."

**Hero quests in IHOGs bear

some resemblance to Joseph Campbell's conception of the monomyth. You can

read more about it at Wikipedia.

copyright © 2011

GameBoomers