Casual Adventures -- Testing the Atmosphere

by Becky Waxman

Having

previously discussed

character and

quest focused games in this series of

casual game editorials, I'm now proceeding to another aspect -- atmosphere.

A

game's atmosphere is surprisingly difficult to define, as the concept is

amorphous and somewhat subjective. I've gathered some ideas below to make a

start.

A

Question of Style

Atmosphere begins with a game's visual style. The palette might be dark and

ominous or bright and colorful. Environments can be stylized or

photorealistic; they can give a sense of three dimensional depth, or they

may be flat and cartoon-like.

Once

an art style is established, texture and depth of the environments further

refine atmosphere -- "a sense of the air around you." Think of the

difference between seeing a photograph of a landscape, and viewing a real

landscape, where you can watch the movement of water in a stream and see the

sun glinting in the leaves. Animation and photorealistic graphics can add to

a sense of realism. But stylized gameworlds can be just as affecting when

they use graphics, animations, and camera angles that are consistent with

the imagined world.

In

The Mood

Atmosphere also embraces mood -- and mood is deeply influenced by music and

other sounds. Remember the landscape mentioned earlier, and picture it with

watery sounds from the rushing stream and birdsong from the trees above.

Ambient sound, like visual animation, gives the effect of a larger world,

full of persistent life. Music (especially if it isn't intrusive) can

manipulate emotions on a subconscious level, adding a sense of uneasiness or

melancholy or urgency or delight.

The

most evocative atmosphere is one in which all these elements -- the setting,

visual effects, camera angles, background music, ambient sounds -- work to

establish a consistent sense of place.

Immersion Needn't Mean Drowning

I've

seen the term "immersion" bandied about even more than the term:

"atmospheric." The two are related: the latter can help to induce the

former.

There

are different levels of immersion. One example: you are playing a game that

has drawn you in. You forget that you are at the computer. You forget what

time it is, what day of the week it is, that you haven't eaten in hours. If

it wasn't automatic, you'd forget to breathe. I call this "breathless

immersion."

I

think there's another kind of immersion -- not as intense, but almost as

engaging. You have spent some time in the game, and you're starting to

adjust. By now the visual style is familiar and the gameworld -- whether

realistic or stylized -- is believable. You feel present in the

environments, or you've begun to identify with the hero/heroine that you

control. You start to anticipate story events and look forward to the next

environment to explore. You're officially hooked. I call this "buying in

immersion." You can buy into a world even if you aren't comfortable with

what you find there -- if it scares, unsettles, or challenges you.

Atmosphere is one factor that eases the gamer into an immersive state,

because atmosphere gives a sense of authenticity and adds to the sensation

of being there. And being there is very close to immersion.

Six

Games that Clarify Atmosphere

To

illustrate these ideas, I've included six games described below that fit

loosely into the "casual adventure" category. Simply playing these games

will give you a better sense of the wide range of mood, visual impression

and, yes, atmosphere available in adventure and casual adventure games.

(Since casual adventures are shorter than "core" adventure games, it's

easier to play them side-by-side or one-right-after-the-other in order to

compare them.)

The

discussion below touches on the effect of visuals, viewpoint, voiceovers,

puzzles, characters and sound. The individual game descriptions also

indicate particular features that add or detract from each game's

atmosphere.

I'll

start with a game that fits the most traditional definition of atmospheric

-- a game set in an isolated wood, in an abandoned asylum, where an ancient

evil spreads its horror.

Nightmare Adventures: The

Witch's Prison

You

assume the role of Kiera Vale, who has just been notified that she has

inherited a family property on which sits the abandoned Blackwater Asylum.

Curious and courageous, Ms. Vale has a sassy modern outlook. Much at the

Blackwater Asylum -- located outside Boston -- has that old-fashioned New

England aura. The place is creepy and decrepit, so our lovely young heroine

is a distinct contrast to her surroundings. The game starts out slowly, with

the full extent of the mystery gradually revealed as you puzzle your way

deeper into the asylum grounds.

The environments in

The Witch's Prison are viewed from straightforward camera angles. The

graphics are naturalistic at first, revealing a gloomy sky, blowing mist,

and a prominent full moon. The visuals gradually become more surreal, with

deep, smudged colors and collage effects. The game draws you into past

iniquities, and you see how modern technology has attempted to deal with

them.

This game is

distinguished by its crucible of puzzles, which bolster the atmosphere of

mystery and decay -- of hidden things that shouldn't see the light of day.

Pattern and code puzzles use occult symbols, and inventory challenges employ

(among other things) bones, poison, and blood. Evidence of the efforts of

others to contain the ancient evil eventually surface, and these create

challenges with a more scientific aspect -- DNA testing, restarting

machinery, and getting past electronic security measures.

This game has a

surprisingly spare touch with one common aspect of atmospheric horror --

sound. Background music is minimal; you mostly hear the ambient sounds:

water flowing, crickets humming, or a wolf howling in the distance. You will

hear occasional voices, but the main character is not voiced. Still, the

story, visual setting, and well integrated puzzles provide the atmosphere

for an unnerving, challenging, engrossing experience.

Do

Puzzles Enhance Atmosphere?

The

puzzles in The Witch's Prison blend well with the environment and

suit the story, so they don't disrupt the atmosphere and they add to

immersion. What about games in which the challenges are distinct from the

environments?

Puzzles that play more like mini-games (rather than integrated challenges)

can bolster atmosphere if they further the story and reveal more about the

characters -- though these are structured to bring engagement in small

gulps, rather than sustained immersion. A good example of this puzzle style

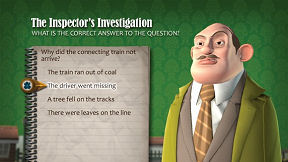

is the Blue Toad Murder Files, which also illustrates how well the

human voice -- arguably the most flexible means for expressing emotion --

can create a compelling atmosphere.

Blue Toad Murder Files

This

game is set in a cartoon-like English village, which you view in 3D flyover

mode, swooping over the grazing sheep and well kept gardens. The atmosphere

is one of pastoral quaintness that overlays a festering secret. You play a

vacationing detective who unexpectedly encounters the eruption of hidden

depravity into...MURDER!

Blue Toad Murder Files

is distinguished by its satiric writing and no-holds-barred humor. Its

atmosphere is hugely bolstered by The Voice, which coaxes, questions,

teases, simpers, and insults. The Voice is Tom Dussek, who does the

voiceover for each character (including the female characters). It's a

remarkable performance -- something like watching Alec Guinness in Kind

Hearts and Coronets, or Patrick Stewart on stage in his one person

production of "A Christmas Carol."

You

never actually walk around the village, but the game takes you overhead and

guides you to each new location, where you interrogate the various villagers

via cut scenes. The puzzles are individual set pieces/mini-games that are

related to each character's needs and concerns. The atmosphere is one of

whimsical tomfoolery, with a certain edginess. You will connect paths,

distinguish differences, solve math problems and figure out anagrams.

Ultimately you must also finger the perpetrator in crimes that range from

leaving dirty footprints on the carpet to...MURDER!

Your

performance is always rated (after failing to find the solution, you can

skip any puzzle if you don't want to try again). When you answer correctly

and within the time limit, The Voice compliments you extravagantly. When you

answer incorrectly or outside the time limit, The Voice scolds you. (You

aren't accused of being The Weakest Link, but the humiliation is roughly

equivalent.)

Of the

six games described in this editorial, this game (despite its comedic tone)

evoked the greatest sense of personal terror. During the cut scenes, I

bought in to the mystery and the humor, but I was subsequently pummeled by

the puzzles. The thrill of victory (achieved by educated guesses to beat the

timer) was outweighed by the inevitable agony of defeat.

Viewpoint and Perspective

Some

gamers find it easier to appreciate the atmosphere and to become immersed in

games in which the viewpoint is from the first person perspective -- where

you are the main character, viewing the gameworld directly. Other gamers

find it easier to immerse themselves in games in which the viewpoint is from

the third person -- where you direct the movements of the character whose

role you are assuming as he or she interacts with the gameworld.

Personally, I find that immersion comes somewhat more quickly in games with

a first person perspective and photorealistic graphics. Below is the game

that, out of the six, provided the style and atmosphere that immersed me

fastest.

The Fall Trilogy Chapter

1: Separation

An explorer has fallen

into a pit somewhere in Asia, losing all memory of the past that might

explain why he is there. Colorful, exotic blossoms, intricate foliage, and

carved stone reliefs ornament the walls. Steam rises from a lava pit below,

and light pours in through openings overhead.

Though photorealistic,

this is an idealized setting of impossible beauty. The game creates an

atmosphere of awe accompanied at first by disorientation. Like the Land of

the Lotus Eaters from The Odyssey, it washes away the past and tempts

you to stay. Mood is established through ambient sound -- birds calling,

water rushing, insects chittering. For "buying in" immersion, this game had

me at hello.

Separation

is a first person perspective puzzle adventure with a handful of category

based Hidden Object challenges. The puzzles include inventory challenges and

mini-games, many based on pattern recognition. (One minor atmosphere

disruption: the optional 360 degree panning feature uses the right mouse

button instead of the left mouse button. I never did get used to it.)

You occasionally hear the

protagonist's thoughts, but his personality is undefined. You puzzle through

the locations alone, except for mysterious voices that sometimes sound as

the screen is infused with a brilliant light. The atmosphere is one of

isolation in a slice of paradise, with reality forcing its way in to jar you

into wishing to escape.

Story, Characters, and Expectations

Characters have a tremendous effect on a game's atmosphere, from their

physical appearance to the way they think and speak and react to events.

Games peopled with many minor characters establish a different mood than

games where the protagonist spends most of her time isolated and alone.

Sympathetic, likeable characters tend to create a lighter tone than

difficult, conflicted characters. Assuming the role of a protagonist who is

a mass of contradictions feels more ambiguous and disturbing than assuming

the role of someone whose actions are predictable.

Plot

also affects atmosphere, creating expectations of what will happen as events

unfold. The gamer anticipates upcoming events with an attitude of

trepidation or curiosity or amusement, etc.

Next up is a game in

which the plot, puzzles and characters aim to amuse and charm.

Royal Trouble

Royal Trouble

takes place in a fairy tale kingdom. The setting is a tropical island under

azure skies, inhabited by a dastardly, shadowy villain. Our two

protagonists, Princess Loreen and Prince Nathaniel, are captives in the

villain's castle. They have never met until they bump into one another while

attempting to escape the dungeons.

Neither Nathaniel nor

Loreen has any compunction about leaving the other behind while scheming to

escape. However, since working at odds with one another results in abject

failure, they conclude that teaming up is their least bad option. Though the

castle and its inhabitants evoke the Renaissance era, the two characters act

and speak with a cheeky, modern attitude.

Loreen is impatient and

high-handed. She is more impressed by the castle's tackiness than by its

owner's cruelty. She thinks Nathaniel can work miracles for her. (She's a

princess, after all.) Nathaniel usually expects the worst, and often finds

it. He calls Loreen "her royal spoiledness," but he's soon resigned to

dashing to her aid whenever she needs him. (He's a prince, after all.)

Dialog between the two and conversations with the eccentric castle occupants

are sarcastic and often pleasingly absurd.

The visual style suits

the fairy tale ambiance. Like the characters, the environments are in

colorful 3D. You'll encounter many inventory item challenges, plus devices

to repair and concoctions to create. The story and gaming challenges call

upon Loreen's wits and Nathaniel's resourcefulness as they improvise their

way through the castle's cellars, kitchens, library, laboratory and towers.

Royal Trouble

is partially voiced through a narrator who, with a suitably droll tone,

relates the background story and comments on the characters as they develop.

The game's only drawback is that the main characters aren't voiced. The mood

is enhanced by background music that reflects the Renaissance era settings;

like the characters and the atmosphere in this game, it is playful, lively

and often comedic.

Embracing the Unfamiliar

and the Suspension of Disbelief

For

readers, the concept of "willing suspension of disbelief" held that the

reader of a story had to work harder to believe in a supernatural world (a

place populated by witches, ghosts or magical beasts, for instance) than in

the real world (a village in England with a freshly murdered corpse, for

instance). An analogy in gaming might be that the gamer has to work harder

to believe in a stylized world -- with hand drawn or cartoon-like graphics

-- than in a naturalistic world with photorealistic graphics.

Atmosphere can immerse, but it can also disturb and challenge. It is a key

factor in forms of entertainment that pull you out of the ordinary and

challenge you with a new way of seeing. Think of the eccentric personal

vision in Tim Burton's films, or the unusual gameworlds in Grim Fandango

or Machinarium -- where the world itself almost becomes another

character in the story.

The two games that follow

are set in hand drawn, surreal worlds with dark themes. Drawn: Dark

Flight is reminiscent of the original tales by the Brothers Grimm. In

it, a lurking evil threatens a kingdom and its innocent young ruler.

Nelson Tethers: Puzzle Agent occupies an absurdist, graphic novel

version of a small town in the U.S., where unknown forces menace the

townspeople.

An intense, quirky

atmosphere is risky. But when it works, as it does in these two games, it's

unforgettable.

Drawn: Dark Flight

The

opening sequence in Drawn: Dark Flight, takes place in the stone

ruins from the original game: Drawn: The Painted Tower. The main

characters are viewed in fragments. Franklin, the caretaker, has been turned

to stone and then broken -- though he can still communicate. You catch a

glimpse of young Iris in a portrait that is turned on its side and partially

obscured.

The visual style provokes

a sense of unease and apprehension. The environments are viewed from a first

person perspective, and much about them is skewed, full of unsettling

angles. Mist blows through empty streets. The houses are larger at the top

than at the bottom, and monumental buildings and statues spring up in odd

places. Animations are frequent: flickering candlelight, drifting sparks,

flying creatures, falling rain. Mood is set by a pensive vocal melody, aided

by melancholy strings. The game is partially voiced. Franklin's gruff

communications are formal and authoritative. He's desperate, and he's

essentially giving you orders. Iris' voice is delicate and sweet, though

also formal.

The puzzles suit the

game's twisted fairy tale style with a focus on the stuff of childhood --

kites, pop-up books, puppet shows -- tinged with the macabre. Sometimes you

use a paintbrush or crayons and draw or fill in shapes. One fiendishly

difficult challenge involves using little gates to let colors leak together

and blend. It had me leaking multicolored tears.

The sense of brokenness

magically disappears each time you enter one of the paintings or tableaus

that Iris has left scattered about the landscape. Once inside these colorful

scenes, the dramatic tone changes; some scenes even add a comedic touch.

This contrast works well, though I felt that I was "really there" in the

brooding city, but outside "looking in" while viewing the paintings. The

paintings indicate what this world was like before Iris' evil nemesis

destroyed it -- a reminder of what has been lost.

Nelson Tethers: Puzzle

Agent

Atmosphere can help take something dramatic or out of the ordinary and make

it plausible. The story events may be absurd -- outrageous even -- but if

the atmosphere, the environment and the character portrayals are consistent,

you can believe.

Nelson Tethers: Puzzle

Agent has an

off kilter, minimalist tone. It opens in the U.S. Department of Puzzle

Research, in the basement of the J. Edgar Hoover Building, which houses the

FBI. Agent Tethers receives a phone call requesting that he go to Minnesota

and investigate the Scoggins Eraser Factory, whose production of erasers for

the White House has unexpectedly ceased. Eraser production must resume or

(presumably) the President won't be able to correct his mistakes.

The characters in

Puzzle Agent are flat and cartoon-like. They have huge googly eyes.

Heavy black charcoal lines frame their figures. Their skin tone changes,

depending on the background color of the environments. Most of the

characters in the town of Scoggins are suspicious of strangers and obsessed

with puzzles. At first this odd behavior seems related to their isolation in

the frozen tundra of this flat, 2D comic strip world. But something far more

sinister is at hand.

The game is played from

the third person perspective. Investigating the town and the factory

presents Agent Tethers with a series of mini-game-like challenges, sometimes

related to the environments (finding passage for his snowmobile, for

instance), and sometimes as requests for help. None are timed. Whenever you

submit a puzzle solution through official channels, you learn the

ridiculously large amount that the American taxpayer pays to check your

answer.

This game is a brilliant

example of the use of sound to create atmosphere. The background music is

techno modern with eerie flourishes that you would expect from an episode of

"The Twilight Zone." It adds a chill to the air and, at times, an odd sense

of self-parody. Ambient sounds include sinister echoes, crunchy footfalls,

and wailing wind. Voiceovers are spot-on, emphasizing Tethers'

straight-as-an-arrow personality and the townsfolks' nutty obsessiveness.

Without sound, this game

is a tongue-in-cheek cartoon puzzle adventure. With sound, it's a creepy

experience, in a place where something out there is not quite right. The

most improbable of situations becomes oddly believable.

Ten

Atmosphere Disruptors

While

playing the six games I've described above, I encountered atmosphere that

immersed me and, occasionally, aspects that broke that immersion. It's a

complex task to integrate visuals, sound, story, characters, puzzles and

interface, resulting in a memorable atmosphere without discontinuities that

hinder the game's progression.

In

fact, disruptions to atmosphere are common; in the fifteen years I've spent

gaming, I've encountered many. Games seem more prone to these problems than

other media because the gamer doesn't just watch what's going on, but also

interacts with what's going on, which can generate barriers and

inconsistencies. The gamer inevitably encounters technical issues with PC

games -- a problem without parallel in other media -- and this also dispels

the effects of atmosphere.

To

conclude this editorial, I've listed ten factors that (all too frequently)

disrupt atmosphere during the gaming experience.

The

Disruptors:

1.

Glitches, crashes and dead ends.

2. A

difficult or innovative movement control interface. (Keyboard-only

interfaces automatically qualify.)

3.

Repetition. Examples: invisible triggers or other puzzle structures that

require extensive backtracking. Timed puzzles that are so difficult as to

cause multiple failures. Dying and having to restart or retry.

4.

Lack of voiceovers for conversations between characters. (It's more

important to voice conversations than to voice the protagonist's thoughts or

hotspot comments.) Bad voiceovers. Inability to click through voiceovers.

Intrusive or inappropriate music.

5.

Lack of ambient animations where they are clearly called for -- fire or

water that is frozen in time. Cut scenes where the characters look very

different than they do in other parts of the game.

6. An

overly helpful hint system or other messages and alerts that you can't turn

off. Frequent or overly long loading screens. Narration or comments on the

player's actions that are snarky or abusive.

7.

Inconsistency in the story. Examples: the characters don't act in accordance

with their established personalities. The storyline doesn't meet the

expectations it has created.

8.

Inconsistency in the gameplay. Puzzle logic that suddenly changes. Interface

functions that morph mid-game. Puzzles that don't mesh with the

environments or the story.

9.

The game fails to get the details right. Examples: a realistic game that

relies on unrealistic scenarios (e.g., ten different types of weapons lying

on a street corner in midtown Manhattan). A historical era game that gets

historical details wrong (e.g., a Victorian era game in which the heroine

uses modern slang). Hidden Object screens with items that don't suit the

surroundings (modern items in games set in pre-modern eras). Dialogs full of

spelling and grammatical errors.

10.

Overwhelming complexity. Puzzles requiring dozens of sequenced steps

performed perfectly. Games in which the interface requires a learning curve,

plus the intricate story is difficult to follow, plus the challenges are

quirky and layered.

Coming Up Next

Look

to this space to see more discussion of casual games. The next installment

in this series: Casual Companions.

*Note: some of the ideas

for this article were influenced by the following articles: "Realism

VS Idealization" by anjin anhut, and "Analysis:

The Psychology of Immersion in Video Games" by Jamie Madigan.

You can find out more

about the willing suspension of disbelief here at

Wikipedia.

copyright © 2011

GameBoomers